By Celia Bernhardt | cbernhardt@queensledger.com

On October 4, the MTA released its 20-year needs assessment and a blow to the QueensLink movement.

The extensive assessment included a section of side-by-side analyses of 25 different proposals to expand, connect, and extend certain parts of the transit system. The Rockaway Beach Branch Reactivation proposal, often referred to as QueensLink, scored low on most of the seven metrics used.

“Reactivating the Rockaway Beach Branch with NYCT service has a high cost and serves a relatively modest number of riders,” the MTA’s evaluation reads. “Compared to other projects, the benefits are average for sustainability and resiliency.”

This comes just a month after a QueensLink rally at City Hall with Queens politicians from both parties voicing their support gave the cause a boost of hope.

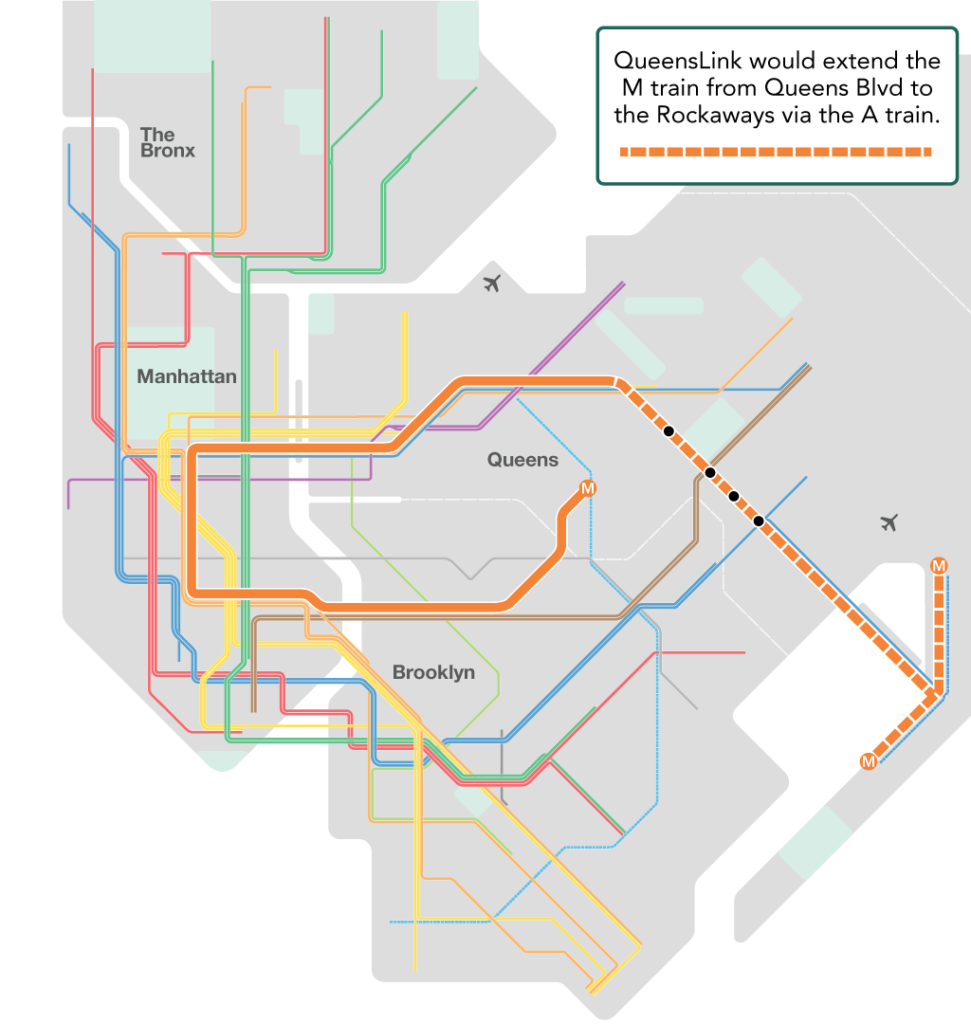

The QueensLink plan would reactivate a railway in Southern Queens left defunct for the past 60 years, connecting the Rockaways to Rego Park—where transit into Manhattan, and transfers to other lines, are available. The proposed line would connect passengers with the A, J/Z, EFR, 7, and G lines, as well as with the LIRR. The plan also includes 33 acres of greenspace and bike paths stretching along the path.

Advocates have been campaigning for years to reactivate the rail. Supporters of the plan emphasize that residents of Southern Queens, severely underserved by public transit, currently have some of the longest commutes in the nation.

Assemblyperson Khaleel Anderson, who represents South Ozone Park and part of the Rockaways in Assembly District 31, slammed the transit authority’s evaluation.

“The MTA has failed, yet again, to figure out how to resolve transportation issues that are impacting some of the most vulnerable working class folks in our city,” he said.

Anderson also pointed out that the lack of easy access to the rest of the borough and to Manhattan isolates many Rockaway residents from economic opportunities.

“You’re talking about transportation apartheid,” he said, and emphasized how impactful the rail reactivation would be. “You’re talking about getting people into the city quicker, you’re talking about opening up more economic opportunities for communities like mine that can’t get to Manhattan and so they can’t take that job opportunity…You’re talking about systemic, drastic changes to how people will move about the city.”

QueensLink’s map of what a reactivated Rockaway Beach Branch rail would look like.

In context

An MTA spokesperson said that the document did not constitute a finalized rejection of the QueensLink proposal.

“The 20 year needs assessment lays out what will be needed in the next capital plan, which is the 2025-2029 capital plan. And we’re kind of letting the findings speak for themselves, for everyone to see,” the spokesperson said. “But it’s not a rejection or a confirmation of any project.”

Still, the Rockaway Beach Branch’s relatively low ranking in a competitive batch of proposals makes it clear that the MTA is not interested in pursuing the plan at this time. The highest ranked proposal by far was the Interborough Express, a project that Governor Hochul has long supported.

The MTA spokesperson said that the comparative analysis of 25 proposals was intended to “give the public more of a broad perspective, and an overview.”

“If you live in Queens, you may be thinking of Queens, and not necessarily think, oh, there are things going on in the MetroNorth. I see why there may be priority for doing work [there] rather than [here].”

Andrew Lynch, Chief Design Officer for QueensLink, argued that a strategy where every borough receives some transit expansion would be more holistic. “Every borough deserves something. Queens probably deserves a lot more considering how big it is and the population…but it’s not one versus the other. It’s ‘What does the total picture look like?’”

Larry Penner, a transportation expert, was not shocked by the evaluation.

“The problem is they’re in competition. If you look at the MTA 20-year needs assessment document, there are [many] other groups equally as adamant and as passionate as the QueensLink people are for their particular project.”

Penner also explained that the process of ranking these proposals is rife with political complications.

“A lot of elected officials support projects where they can have ribbon cutting ceremonies and get the support of voters,” he said, and pointed out that the governor, who appoints the MTA’s leadership, has significant sway over such decisions.

Two central issues at hand as the MTA assesses a future for its weakened infrastructure are the threat of severe weather from climate change, and a growing, shifting city population in need of expanded transit options. Ultimately, the document emphasizes that funding for any expansion projects at all remains contingent on the MTA’s process of repairing existing infrastructure.

“As we look ahead 20 years, our most urgent priority is to secure the survival of our existing system by rebuilding its most imperiled infrastructure,” the document reads. “To put it bluntly, unless sufficient resources are made available to address the existing system’s most urgent needs, there cannot be investment in expansion projects.”

Penner, for his part, does not think that QueensLink, nor the Interborough Express, nor any other expansion project should be seriously considered right now.

“It’s definitely not [appropriate] given the tremendous shortfall in safety and state of good repair,” he said.

Queensway in the way

The MTA’s evaluation specifically pointed to QueensWay plans as one reason not to reactivate the train line. A “Special Considerations” section reads: “New York City-owned right-of-way: plans for a linear park along portions of the corridor, creating a challenge for any future transit alternatives.”

The QueensWay plan, a long time competitor to QueensLink, would convert the abandoned rail entirely to parkland, similar to the Highline in Chelsea. In September 2022, Mayor Adams pledged $35 million to the plan—much to the dismay of QueensLink supporters, who argued that moving forward with the park would create an obstacle to ever reactivating the branch for transportation use. Several statements from City Hall spokespeople, elected officials, and MTA officials throughout the following year denied that moving forward with Queensway funding would preclude the revival of the train line.

In a statement following the needs assesment’s release, Rick Horan, Executive Director at QueensLink, said his team had “always been skeptical” of these reassurances. “Today, that skepticism has turned into grave confirmation,” he said in the statement.

Adams announcing $35 million in funding to QueensWay in 2022.

The organization Friends of Queensway provided the following statement: “The objective analysis released in the MTA’s Needs Assessment is consistent with multiple other studies done on rail reactivation over 60 years in concluding that it would be extremely expensive, have little actual impact on mobility as compared to other regional transit projects, and would have negative impacts on the environment and quality of life. The sends a clear message on the best use of the Rockaway Beach Branch line at this time. The parks and trails QueensWay project is ready for implementation and would not harm any effort to reactivate the site for rail in the future should the government decide to do so.”

Data divergence

The MTA’s report came up with contrasting numbers to QueensLink’s: whereas the transit advocacy group stated in a press release that 47,000 daily riders would benefit from the plan (a number they pulled from the MTA’s own 2019 feasibility study of the train route), the MTA now puts that number at 39,000. QueensLink also said that the train would save riders an average of 30 minutes per round trip, while the MTA said only four minutes would be saved. And while QueensLink’s assessment put the estimated cost of the project at $3.5 billion, the MTA listed it as $5.9 billion (a decrease from its 2019 estimate of $8.1 billion, which QueensLink hotly contested).

“There was so little information provided in the needs assessment that we requested background data from the MTA so we have something to analyze,” Horan said. “All we have are conclusions that don’t make sense to us, so unless we get some data so we have some idea as to how these conclusions were reached, we’re really flying blind.”

QueensLink’s own numbers were calculated by TEMS, a transportation consulting firm they commissioned to produce a study in response to the MTA’s also-pessimistic 2019 feasibility study of the train route.

What’s next?

Horan explained that QueensLink has long been asking for the city or state government to pursue an Environmental Impact Statement or Economic Impact Statement about the project, and that it’s still needed. Anderson and Lynch also emphasized the importance of such studies. “Commission a real study,” Anderson said. “Not a study where you have already set it before the pencils are picked up.”

Penner said that pressuring Queens elected officials to channel funds into these studies would be strategic.

“If the QueensLink people want to hold elected officials accountable—any elected official could provide the MTA with seed money to advance the project and go through an environmental review process.”

Anderson argued for increased ferry services and express bus transit from the Rockaway peninsula as an alternative to rail transit.

“If they don’t like QueensLink so much, what is their alternative that people are presenting?” he asked.

Lynch says that despite the MTA’s evaluation, he remains optimistic. “This really doesn’t change anything. It doesn’t change our position, it doesn’t change the overall narrative of the MTA’s feelings towards this project.”

“We’re disappointed,” he continued. “But it’s also, like, I’m not surprised at all. The thing that this project has lacked in the past is a political champion, and projects like this don’t get built without those. But the difference between now and, let’s say, five years ago, is that there’s a lot more support in the community, there’s a lot more support politically. And there’s an understanding that it’s a lot more feasible than people thought…we still have a lot of work to do to build more support for this project in the communities and in Albany, and we’re going to continue on that.”