Flushing playwright writes memoir

By Daniel Offner

doffner@queensledger.com

Growing up in Flushing had a profound impact on Alvin Eng, a local author, playwright, performer, educator, and punk rock raconteur, whose family was one of only a few immigrant Chinese families to move into the community at the time.

His parents were from a different generation. They had an arranged marriage and moved to New York from a different part of the world, during a time when U.S. laws restricted Chinese immigrants from becoming full-fledged U.S. citizens. Here they faced numerous obstacles all while raising five kids and operating a successful hand dry laundry business at 29-10 Union Street.

Eng said he didn’t learn how to speak and write Chinese as a kid, because he was desperate to try and fit in. His first experience with the literary world came unexpectedly when he was just a 17-year-old reporter working for the Flushing High School newspaper.

Thanks to a chance interview with a music pioneer, he quickly found himself deep in the heart of New York City’s burgeoning punk music scene in the ‘70s.

“I was very lucky. David Johansson of the New York Dolls and Buster Poindexter, let me interview him at 17 and that changed my life,” Eng said. “All the misfits at that time went to the punk rock world.”

Known for being rebellious and loud, it was the perfect place for a teenager. Eng was enamored by the culture and began incorporating it into his work.

He began writing plays in the ‘80s, after being invited to a production of David Henry Hwang’s Broadway hit, “M Butterfly,” and once again, his life was forever changed.

It was not long after that when Eng wrote his first stage play, a punk-rap musical entitled, “The Goong Hay Kid,” which he performed at a number of small venues across NYC including the Nuyorican Poets Cafe in 1994.

His next production was titled, “The Flushing Cycle,” which he went on to perform at Queens Theatre in the Park in 2000 and the Pan-Asian American Theater. His performance, in essence, would form the basis of his forthcoming memoir about his childhood, which is told through a series of spoken-word monologues and poems.

Eng said that he lost his father when he was just 14, which dramatically changed his relationship with his mother. He took care of his mother for a long time, and in 2002, when she died, he decided he would write a little more about her.

His next play, “The Last Emperor of Flushing,” was based on his mother, whose real-life relationship played a tremendous influence on his work. Since 2005, he has performed the play to several crowds all across New York City and other parts of the country.

“I wrote about a lot of issues I faced as an Asian-American,” Eng explains. “But I didn’t want to only write about identity issues.”

In that regard, he went on to write a series of “portrait plays,” which explore and dramatize the parallels between portraiture, history, and power as manifested in the convergence of different disciplines, eras and cultures.

As both a theatrical practitioner and professor, Eng found himself intrigued by the under-chronicled influence China played on Thronton Wilder’s classic production, “Our Town,” which became an unexpected catalyst for his psyche-healing pilgrimage to the City University of Hong Kong.

There, both he and his wife, Wendy Wasdahl, led a Fulbright Specialist devised theater residency to teach Chinese students how to write and perform English language plays in response to Wilder’s theatrical masterwork.

It was thanks to this residency that in 2011, the U.S. Consulate in Guangzhou, China, extended an invitation to Eng to come and perform “The Last Emperor of Flushing” memoir monologue in his family’s ancestral Guangdong Province.

His latest work, “Our Laundry, Our Town” is a prose-style memoir of his life, from his childhood in Flushing to his productions on the Downtown Stage and beyond.

“In some ways, my parents’ arranged marriage was the ultimate tragic opera in that I never once saw them dance or engage in any amorous way that went one breath or gesture beyond the bare-bones necessities of running our laundry and our family,” Eng said. “In another sense, theres was an unmitigated immigrant success story in that they both ventured to the other side of the world at a time when our race was legally blocked from becoming U.S. citizens for almost an entire century, and propsered. Against mountains of society, institutional, and legal obstacles, they raised five children and maintained a successful mom-and-pop Chinese hand laundry business for three decades, as well as two homes.”

His book, which explores his parents relationship and growing up in Flushing, Queens, will be released by Fordham University Press on May 17.

His book, which explores his parents relationship and growing up in Flushing, Queens, will be released by Fordham University Press on May 17.

Eng said that following the book’s release, he plans to host readings featuring excerpts from the story. The first, he said, will take place at the independent bookseller’s Kew and Willow, located at 81-63 Lefferts Blvd., in Kew Gardens on May 26.

In terms of what comes next, Eng said “we’ll see. I would love to see if a film could be made out of this.”

For now, Eng is busy working on a new performance piece entitled “Here Comes Johnny Yen Again (Or How I Kicked Punk),” The title, which takes its name from character created by William S. Borough’s, explores the impact that opium played on the Chinese Diaspora and the NYC underground punk culture through the dual prisms of the character––immortalized by the Iggy Pop/David Bowie classic “Lust of Life”––and his grandfather’s opium overdose on the streets of Chinatown.

The first workshop performances were performed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, while additional performances planned for April were cancelled.

He is also in the early stages of writing a new play, entitled “AARP (Asian American Rock Party) Presents a One-Night Reunion of G.O.D. (Goddess Of Democracy),” which features original new music and is told, chanted, ranted and sung from the perspective of “Goddess of Democracy,” an early ‘90s alt-rock band that performed in the wake of the 1989 Tianmen Square uprising.

To find out more about the author, visit his website alvineng.com.

The young Manhattan-based entrepreneur says he discovered Citi Bike’s fleet of e-bikes last summer and has been riding ever since.

The young Manhattan-based entrepreneur says he discovered Citi Bike’s fleet of e-bikes last summer and has been riding ever since. Laura Fox, the general manager of Citi Bike, outlined some of the new features of the revamped e-bikes, which include a longer-lasting battery life up to 60 miles and a reflective-paint that is highly-visible at night.

Laura Fox, the general manager of Citi Bike, outlined some of the new features of the revamped e-bikes, which include a longer-lasting battery life up to 60 miles and a reflective-paint that is highly-visible at night.

The Flushing resident and single mother of one says she was fired after she called in sick, despite having three sick days to use. In response, Service Employees International Union Local 32BJ filed charges under the National Labor Relations Act, accusing Chipotle of firing her for union activity.

The Flushing resident and single mother of one says she was fired after she called in sick, despite having three sick days to use. In response, Service Employees International Union Local 32BJ filed charges under the National Labor Relations Act, accusing Chipotle of firing her for union activity.

“My biggest goal was to be an art director for a major magazine,” she says, adding that she stayed in Des Moines to take a job with the media conglomerate Meredith Corp.

“My biggest goal was to be an art director for a major magazine,” she says, adding that she stayed in Des Moines to take a job with the media conglomerate Meredith Corp. There are shiny silver scoops and funnels for the dry goods.

There are shiny silver scoops and funnels for the dry goods.

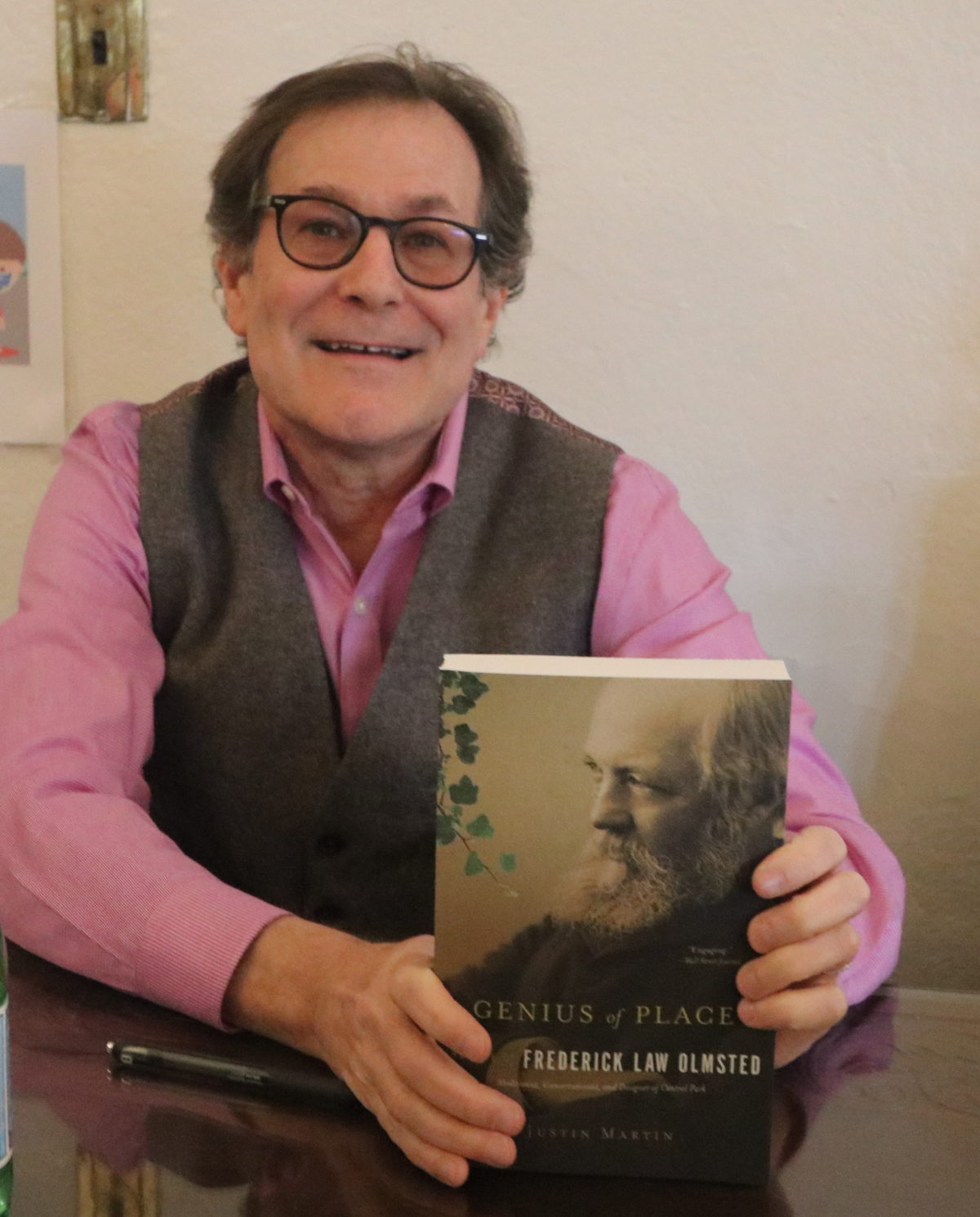

Olmsted was born on April 26, 1822, in Hartford, Ct., and passed away on August 28, 1903, in Belmont, MA. Among his most significant accomplishments are the landscapes of Central Park, Riverside Park and Drive, Prospect Park, Bayard Cutting Arboretum in Long Island, Ocean Parkway and Eastern Parkway, Morningside Park, Downing Park in Newburgh, the U.S. Capitol, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, and the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. His son, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr, designed Forest Hills Gardens, along with principal architect Grosvenor Atterbury.

Olmsted was born on April 26, 1822, in Hartford, Ct., and passed away on August 28, 1903, in Belmont, MA. Among his most significant accomplishments are the landscapes of Central Park, Riverside Park and Drive, Prospect Park, Bayard Cutting Arboretum in Long Island, Ocean Parkway and Eastern Parkway, Morningside Park, Downing Park in Newburgh, the U.S. Capitol, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, and the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. His son, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr, designed Forest Hills Gardens, along with principal architect Grosvenor Atterbury. That is the site of Olmsted’s farmhouse at 4515 Hylan Boulevard and farm, which was home from 1848 to 1855. Tosomock Farm is where he began experimenting with landscaping and agricultural techniques, resulting in improvements that influenced his later countrywide designs. Today this rare survivor is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is awaiting significant restoration. Martin serves on the board of an organization committed to restoring it. He said, “we are also hoping to open it as a museum dedicated to agriculture and its most famous resident.”

That is the site of Olmsted’s farmhouse at 4515 Hylan Boulevard and farm, which was home from 1848 to 1855. Tosomock Farm is where he began experimenting with landscaping and agricultural techniques, resulting in improvements that influenced his later countrywide designs. Today this rare survivor is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is awaiting significant restoration. Martin serves on the board of an organization committed to restoring it. He said, “we are also hoping to open it as a museum dedicated to agriculture and its most famous resident.” When the Civil War ended in 1865, communities countrywide began clamoring for parks to be built. He explained, “Communities wanted their ‘Central Park.’ It was like a dam bursting. The natural team to turn to was Olmsted & Vaux, and they produced a series of masterpieces across the country. Their sophomore initiative was Prospect Park.”

When the Civil War ended in 1865, communities countrywide began clamoring for parks to be built. He explained, “Communities wanted their ‘Central Park.’ It was like a dam bursting. The natural team to turn to was Olmsted & Vaux, and they produced a series of masterpieces across the country. Their sophomore initiative was Prospect Park.”